Spend enough time investigating online fraud, and you start to notice a pattern. Before any major scheme breaks out, there’s always an early formation stage where actors test, share, and refine their methods before launching at scale. Credential stuffing, check alteration, synthetic identities, phishing kits—they all take shape during this phase, emerging in closed forums, encrypted channels, and underground marketplaces where new methods are tested and refined.

The signals are there if you know where to look. The problem is that most organizations never see them.

For years, fraud-intelligence programs have leaned on static data feeds: lists of artifacts, data, and reports that arrive on a fixed schedule. These feeds validate what’s already known, but they rarely capture the signals that matter in time to act on them. They’re designed to summarize, not to discover.

Meanwhile, the actual innovation in the fraud ecosystem happens somewhere else: in invite-only Telegram channels, dark web markets, and regional-language forums that update in real time.

By the time a static feed flags a new technique, the damage is often already done.

How Fraud Really Evolves

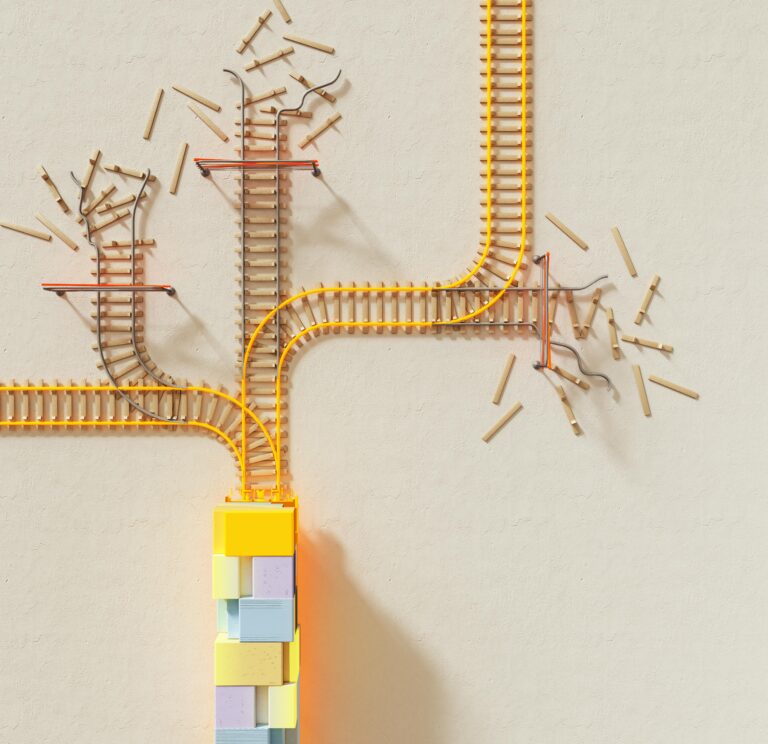

Fraudsters don’t invent tactics in isolation, they crowdsource them. In closed forums, encrypted chat groups, and dark web marketplaces, one actor might test a new way to spoof a bank’s mobile login, another experiments with bypassing two-factor authentication, and a third packages those ideas into a tool or service. What starts as a handful of code snippets quickly becomes a repeatable process.

That’s how these playbooks—malicious, step-by-step guides or tutorials that are shared or sold across fraud communities—emerge. Once that happens, scale is inevitable. What was once a handful of isolated attacks turns into thousands of coordinated attempts overnight.

Every fraud analyst knows that moment when an unknown tactic suddenly floods detection systems. The frustrating part is realizing that the warning signs were online weeks earlier; they just never made it into the static data feeds they were relying on.

Why Static Feeds Miss the Mark

Static feeds give teams a sense of control, but it’s often an illusion. The collection sources are fixed, the cadence is slow, and the data is usually stripped of the context that matters most.

A feed might tell you that an email address or domain is linked to a certain TTP, but not how the tactic was built, who’s promoting it, or how it connects to your own organization’s exposure. In essence, you’re looking at the exhaust, not the engine.

And when you’re responding to fraud, that lag time, which is the difference between seeing something tested in a small community and seeing it deployed at scale, is expensive. I’ve watched organizations lose millions cleaning up after an attack that could have been spotted earlier if their intelligence collection wasn’t stuck waiting for someone else’s update cycle.

A Different Way to Collect

Primary Source Collection (PSC) changes the equation by giving intelligence teams the ability to shape collection around the questions that matter most to them, whether those questions come from security operations, fraud prevention, compliance, or executive leadership. It’s a method for collecting directly from the original spaces where actors operate and trade information, ensuring the data aligns with the organization’s priorities before it’s filtered, delayed, or summarized elsewhere.

That means tasking your intelligence team to go where the activity is, whether that’s a closed forum advertising check alteration services or a new invite-only group exchanging tutorials on identity fraud. The goal is to collect from the source while the discussion is still unfolding.

One financial institution that adopted this approach discovered counterfeit checks featuring its logo being advertised weeks before customers started reporting losses. By monitoring those underground spaces directly, analysts could flag the images, trace the sellers, and alert internal teams early enough to prevent further exploitation.

That’s what early warning actually looks like.

Making Intelligence Taskable

One of the core advantages of PSC is control. Teams can define a Priority Intelligence Requirement (PIR), such as “Identify actors selling bypass methods for our login flows,” and then immediately direct collection toward that need. PSC allows analysts to rapidly discover new, relevant sources and begin gathering intelligence the moment a requirement emerges. They’re no longer waiting for a provider to decide what’s important; they’re defining their priorities and expanding visibility in real time to meet them.

That shift turns intelligence from a passive stream into an operational asset that lets analysts test hypotheses, confirm suspicions, and uncover tactics before they mature. It also gives leadership something more valuable than indicators: confidence that their teams aren’t blind to what’s developing just out of sight.

Spotting Fraud Campaigns Before They Scale

The earlier you can observe a tactic in the wild, the earlier you can defend against it. When fraud actors start discussing a new bypass technique or bragging about a successful test, that’s the moment to act — not weeks later when the same method is being resold across markets.

PSC provides that window. It surfaces the chatter, screenshots, and proofs-of-concept that reveal what’s coming next, and gives analysts the ability to watch innovation happen in real time, which in turn gives fraud teams a chance to intervene before the attack cycle matures.

Why This Shift Matters

Fraud operations have become faster, more collaborative, and more automated. The barrier to entry is lower, the tooling is better, and the pace of experimentation rivals legitimate tech development, so defenders can’t afford to move slower than the adversaries they’re trying to stop.

Primary Source Collection is how intelligence teams keep up. It doesn’t replace analytics or automation, but feeds them with earlier, richer insight. It turns intelligence into a proactive function that helps prevent losses instead of simply documenting them.

For those of us who’ve spent years watching fraud evolve in real time, the value is obvious. The signals are out there — they always have been. The challenge is surfacing them early in their lifecycle, when action can still change the outcome.